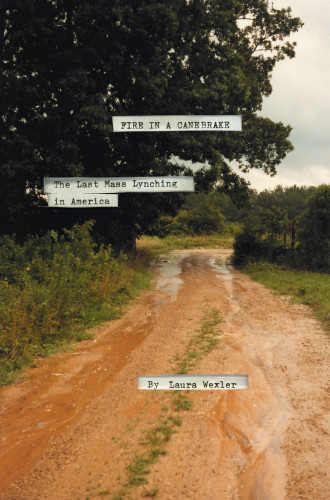

Excerpt from Fire in a Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America

Chapter One

“I don’t want any trouble,” said the white man, Barnette Hester.

He stood on one side of the dirt road and his two black tenants, Roger and Dorothy Malcom, stood on the other side. They were shouting and cursing, their voices echoing through the Sunday evening quiet. The noise had reached Barnette Hester in the barn. He’d stopped in the middle of evening milking, run out to the road, and issued his warning.

At twenty-nine, Barnette Hester was tall and thin, so thin he appeared boyish, as though his body hadn’t yet filled out. His three brothers were broad-shouldered men who spoke in booming voices, but he, the youngest, was shy to the point of silence-except on Saturday nights, when he drank liquor, and talked and laughed a little. He’d been born in the modest house across the road, and never left. When the other boys his age went off to the war, he stayed home to help his parents, and his father made him overseer of the family farm. They owned one hundred acres: a few behind the house, and the rest beyond the barn. That afternoon, after returning from church, Barnette had walked through the rows of cotton and corn and made the same conclusion farmers all over Walton County were making: it was the beginning of lay-by time. The crops were nearly full-grown, and fieldwork would be light for the next month or so, until the harvest.

When it was harvest time, Barnette would stay in the fields from sun-up to sundown, snatching the cotton from the bolls and stuffing it into burlap croker sacks. And Roger and Dorothy Malcom would work alongside him. As children, Barnette and Roger had been playmates. But in January, when Roger and Dorothy moved onto the Hester farm, they’d become Barnette’s tenants. Once earlier in the spring, he’d found them fighting in the road in front of his family’s house and told them to go home-and they obeyed. They walked to the forks in the road, took the path down a small hill, and went inside their tenant house. Barnette issued the same warning this evening, and he expected the same reaction.

Instead, across the road Roger Malcom charged at Dorothy with his arm outstretched. She dodged him, then ran down the road, into the front yard of the Hester’s house. As she passed, Barnette heard her say, “Roger’s gonna kill me.”

Roger went after Dorothy. He followed her into the Hester’s yard, and to the big fig tree, where he lunged at her again. Just then, Barnette’s wife, Margaret, stepped out the front door of the house onto the porch. She watched Roger and Dorothy in the yard for a moment, and then she looked up and called to Barnette. “He’s got a knife,” she said, “and he’s going to cut her.”

Barnette crossed the road and entered the front yard. When he neared the fig tree, Dorothy darted onto the porch where Margaret stood, and both women rushed inside, leaving only Barnette’s seventy-year-old father on the porch. Roger started toward the porch, and Barnette hurried to catch up with him. He stepped close, smelling the liquor on Roger’s breath. He put his hand on Roger’s arm, and tried to turn him back toward the road. “Get out of the yard,” he said. And then, for the second time: “I don’t want any trouble.”

Roger Malcom shrugged off Barnette’s hand and hunched over. Then he spun around and charged, his arm outstretched.

The blade of the pocketknife entered the left side of Barnette’s chest, just below his heart.

After Roger Malcom pulled out his knife, he threw his hat on the ground. From the porch, Barnette’s father heard him say: “Call me Mister Roger Malcom after this.” Then he ran away.

When Barnette clutched his side and began stumbling toward the house, his father, Bob, assumed Roger Malcom had hit him hard in the stomach. Neither he, nor anyone else in the Hester family, realized that Roger Malcom had cut Barnette-not until Barnette collapsed onto the porch. Then Margaret saw the blood, and cried out, “Take my husband to the hospital. He’s bleeding to death.”

Barnette’s eldest brother, George, who was visiting from next door, came onto the porch. Together, he and his father carried Barnette out to the car and lay him across the back seat. Pulling out of the driveway, they turned toward the hospital, located nine miles away in the Walton County seat of Monroe.

By then, the white people who lived near the Hesters had heard the commotion. These neighbors-whose surnames were Peters, Adcock, Malcom, and also Hester-were related to Barnette’s family and each other by blood or marriage, or both. Their ancestors had claimed farms in this section of the county during the land lottery of 1820, and they’d set their modest frame houses close to each other and to the road, preserving every inch of dirt for cotton and corn. The settlement had been dubbed Hestertown in the early days, and the name stuck because the families stayed. In 1946, roughly thirty Peters, Malcom, Adcock, and Hester families still lived along Hestertown Road. Some of the young men drove fifty miles each day to work at factories in Atlanta, and other men and women worked at the cotton mills in Monroe-but they remained in Hestertown and remained tied to the land and community. On this July evening, some had been gathering vegetables in their gardens, preparing for the evening meal, when they heard the disturbance at the Hester house. Now they walked out from their farms to see if they could help.

Barnette’s cousin, Grady Malcom, had already reached the road when the car carrying Barnette passed by. “Get Roger,” Bob Hester called out the car window, “because Roger stabbed Barnette.”

Grady Malcom, in turn, called to his brother, and together the two men, both in their fifties, ran toward the Hester’s house. When they saw Roger Malcom dart into a nearby cornfield, they followed him to the edge. Then they stood there and yelled to him. “Throw down your knife and come out,” they said.

From deep in the corn stalks came the muffled sound of Roger Malcom’s voice. “Who are you?” he asked.

When the brothers shouted their names, Roger Malcom said he wouldn’t come out. But then, after a few minutes, he stood, tossed his knife to them, and surrendered.

By the time the brothers took Roger back to the Hester’s front yard, a crowd of neighbors had gathered. One man drove to Adcock’s store down the road to telephone the sheriff’s office. Another man held Roger down while several others bound his hands and feet. Like Barnette, they’d known Roger Malcom for years, and they knew he was a fast runner-fast as a rabbit, everybody said.

It was nearly dark when Walton County Deputy Sheriffs Lewis Howard and Doc Sorrells pulled into the yard. They untied Roger Malcom, handcuffed him, put him in the backseat of their patrol car, and drove off in a cloud of dust.

The sheriffs retraced the route Barnette Hester’s father had taken one hour earlier, driving the mile to the end of Hestertown Road, and turning onto Pannell Road. Heading northeast, they traveled through the heart of Blasingame district, which lay near the southern point of diamond-shaped Walton County, and contained the county’s richest farmland. In Blasingame, as in the county itself, farmers planted corn, small grains, and timber-but their livelihood depended almost entirely on cotton. Since the beginning of agriculture in Walton County, cotton had been the major cash crop, comprising roughly eighty-five percent of the county’s total agricultural profits each year. Under the guidance of the local extension agent, farmers planted only certain varieties of cottonseed and used only certain fertilizers, and their care paid off. Year after year, Walton County ranked at the top of Georgia’s cotton-producing counties. In 1945, the county’s farmers had produced more than a bale per acre on average, shattering every cotton record in state history.

By 1946, farmers further south and west had begun to employ mechanical cotton pickers, which did the work of forty farmhands, more quickly and more cheaply. But the rolling hills of Walton County, which was perched on the midland slope between the flat fields of middle Georgia and the mountains of north Georgia, made mechanical cotton pickers unusable. And so, despite the innovations-electricity, automobiles, radios-that had modernized much of rural life in Walton and its surrounding counties, farmers still depended on human labor to pick their cotton. In that respect, the harvest of 1946 would be no different than the harvest of 1846.

Within fifteen minutes of leaving the Hester house, the sheriffs had left the fields of Blasingame behind, passed a small forest known as Towler’s Woods, and were entering the outskirts of town. They crossed over the railroad tracks-where several trains daily made the roughly forty-mile trip between Monroe and Atlanta-and drove by the town’s two cotton mills, hulking brick structures that employed eight hundred white people. At times the mills ran day and night, but it was Sunday evening, and they were still.

A few blocks west, the sheriffs entered Monroe’s downtown, a grid of paved streets containing banks, a department store, a hardware store, a pharmacy, and several restaurants. These were the standard establishments found in every county seat or trading center of the day, but Monroe had more to offer than most. It had two public libraries and two public swimming pools-one for Colored-as well as a city-owned ice plant, meat locker, and power and light system. Though a small town, with a population just under five thousand, Monroe boasted ten lawyers, fifteen doctors, and more than one hundred teachers. It was known throughout Georgia as a wealthy and progressive town, the first in the state to offer a groundbreaking public health care program for both white and black citizens. And, as the birthplace of no fewer than six of the state’s former chief executives, it had earned the nickname Mother of Governors.

Monroe’s prosperity was partly due to the continued success of Walton County’s farmers, who drove into town weekly to do their banking and buying. But it was also a result of its location as a midpoint on the highway that connected Atlanta, to the southwest, with Athens, to the northeast. Since its completion in 1939, the Atlanta-Athens highway had funneled tourists and businessmen through downtown Monroe, where they mingled with the locals in the shadow of the town leaders’ pride and joy: a stately brick courthouse topped by an elegant four-sided clock tower. Recently, Monroe had also earned bragging rights with its new electric street lamps, which were aglow as the sheriffs drove through town with Roger Malcom.

Earlier in the day, men, women, and children dressed in their Sunday best had filled the pews of Monroe’s thirty-six churches; the town fathers were proud to report that ninety-five percent of the town’s citizens belonged to a church. After morning services, the streets emptied, and Sunday evenings, as a rule, were quiet. But on this Sunday evening, downtown was bustling. Groups of white men stood on the street corners, and clustered around the Confederate memorial on the courthouse square. Some passed out pamphlets, signs, and bumper stickers; others gave impromptu speeches in support of Eugene Talmadge or James Carmichael. These were the two names on most Georgians’ tongues that summer, the two lead candidates in the most hotly-contested governor’s race in state history. It was July 14th. The election would take place in just three days.

The sheriffs turned onto Washington Street, drove two blocks north of the courthouse, and parked in back of the two-story cinder-block jail. Deputy Sheriff Lewis Howard, who served as the county jailer, took Roger Malcom from the car and led him into the group cell on the jail’s first floor. After locking him in with two white prisonerse-the county jail wasn’t segregated by race-he walked down the hallway leading to the adjoining brick house where he lived with his family, and secured the heavy metal door behind him.

Across town late that Sunday night, two doctors left the operating room and met Barnette Hester’s father and brothers in a corridor of the Walton County Hospital. They didn’t have good news. The blade of Roger Malcom’s pocketknife had sliced through the upper region of Barnette’s stomach, lacerating his intestine and puncturing his lung. The doctors had washed the protruding section of intestine and reconnected it. Then they’d inserted a tube to drain the fluid in the lung.

The risk of infection was grave, the doctors said. They weren’t sure Barnette would live out the week.

Chapter Two

Earlier that Sunday, Roger Malcom had set off with Dorothy and his 74-year-old grandmother, Dora Malcom, for the trip from their tenant house on the Hester farm to Brown’s Hill Baptist Church. The tiny frame church sat in a ravine at the edge of Hestertown, down from Union Chapel Methodist church, where many of Hestertown’s white families worshipped. On their way to Brown’s Hill, the black people had to pass Union Chapel. As they did, their white landlords often called to them, saying they ought to be working in the fields instead of going to church. But it was just talk. No one, white or black, worked on Sunday.

Roger, Dorothy, and Dora Malcom-whom Roger called Mama Dora-had only been walking for a few minutes that morning when Mama Dora’s feet began to ache. She continued on along the path that led up the hill from the tenant house, but when she reached Hestertown Road, she stopped and said she couldn’t go any further.

As Mama Dora started back home, Dorothy left Roger’s side and ran to join her. Roger asked Dorothy to stay with him. When she said no, he yelled at her. When she still refused, he turned and continued walking. “I’m going on without you,” he said. “I was going to leave you in the fall anyway.”

Roger Malcom was twenty-four years old, and had lived in Hestertown since the day in 1924 when he and his parents moved onto the Malcom farm, which lay roughly a mile from the Hester’s place. Soon after they arrived, Roger’s father ran off with another woman. A year after that, his mother died. Mama Dora took two-year-old Roger and his sister on as her own children, and the Malcom family gave them their surname. Roger Malcom’s name at birth had been Roger Patterson, but few people in Hestertown-black or white-knew that.

As a child, Roger had been treated kindly by his white landlords. In fact, some white people in Hestertown said the landlord’s wife had spoiled him by treating him too much like her own son. He’d had to work in the cotton field as soon as he could hold a croker sack, but he’d been allowed to play with the other black and white children in Hestertown, including Barnette Hester. That changed in 1931, when Barnette’s older brother, Weldon, became the overseer at the Malcom farm, and introduced nine-year-old Roger to the beatings and floggings that would be a regular feature of his life for the next fifteen years. One particularly brutal beating occurred on a day in 1937, when Weldon Hester threatened to whip Mama Dora for slacking in the fields. After Roger picked up a hoe to protect her, Weldon Hester attacked him instead. That day Roger fled to the town of Mansfield, in the next county south, but Weldon Hester found him, and forced him to return to the farm. A few years later, Weldon Hester threw Coca-cola bottles at Roger in Adcock’s store after he refused to haul wheat on a Sunday. He’d have beaten Roger further if a few white men hadn’t restrained him.

In 1943, at the age of twenty-one, Roger married Mattie Louise Mack, a young black woman he’d met at Brown’s Hill church one Sunday. She left the farm in Hestertown where she’d been working, and moved in with him and Mama Dora on the Malcom place. In January 1944, she gave birth to a son named Roger Jr.. Eighteen months later, when she ran off to Atlanta, Roger had already met Dorothy Dorsey. She moved in with him and Mama Dora, and despite the fact that Roger and Mattie Louise were still legally married, began calling herself Mrs. Roger Malcom.

Then, in December 1945, Weldon Hester informed Roger and Dorothy that they’d have to move off the Malcom place; he’d rented out the farmland, and no longer required their labor in the fields. Luckily, Barnette Hester needed hands on the Hester’s family farm down the road. So Roger and Dorothy loaded up a wagon with furniture, and moved into the tenant house that sat down a hill from Hestertown road. Since January, Barnette Hester had paid Roger by the day for his fieldwork, and paid Dorothy by the week for cleaning, cooking, and helping care for his two young children. Roger and Dorothy also had a cotton patch on the Hester place. They’d planned to use the proceeds from the sale of that cotton-minus what they owed Barnette Hester for rent, seeds, and fertilizer-to get to Chicago, where Roger’s sister had moved. But lately Roger had begun to consider going to Chicago alone. And, after Dorothy turned back, he had one more reason.

In fact, he was so angry after Dorothy left that morning that, instead of walking to Brown’s Hill, he went to a nearby farm to buy a jar of bootleg liquor. He carried the liquor to a friend’s house, and started drinking and talking about his troubles. The more he drank, the angrier he got. Finally he told his friend that Dorothy was running around on him. “She is going with a white man as sure as you’re born,” he said.

Roger Malcom’s friend wasn’t surprised by this revelation. Earlier in the summer, he’d seen Dorothy curse at Weldon Hester on the road, and when Weldon Hester didn’t retaliate-didn’t beat her, didn’t even threaten to beat her-he’d immediately suspected they were having sexual relations. Other black people in Hestertown believed Dorothy was having sex with Barnette Hester-not Weldon Hester. They claimed they had relations while she worked in the Hester house, and Roger worked in the field. Dorothy herself had once told Roger’s sister, Dora Mae, that Barnette Hester had given her liquor. Dora Mae assumed Dorothy had given him something in return. Even Mama Dora thought Dorothy was “fast.”

But still others in Hestertown had heard that Dorothy had tried to fight off Barnette Hester, that he’d forced her to have sex with him. They’d heard she told him: “Quit bothering me, before the other hands know about this mess.” They knew the tradition; they knew their mothers, sisters, and wives-or they themselves-had been forced to do likewise on the mornings or afternoons when the white landlord sent the men in their family to the most distant field on the farm. Some even suspected Roger Malcom was going to be killed so one or both of the Hester brothers could have even easier access to Dorothy.

No doubt Roger and his friend discussed these possibilities that Sunday before Roger left to visit his old friend Allene Brown, a black woman who lived on a nearby farm. In Allene Brown, Roger found a sympathetic ear; she’d harbored suspicions about Dorothy for a long while. “She always go with white folks,” she says. “I told her to leave them alone.” But even though she agreed with Roger, she tried to convince him not to confront Dorothy. He kept saying he was going to get her from Barnette Hester, and that scared Allene Brown.

“Don’t go,” she told him.

“I’m going,” Roger Malcom said, “if I have to die with my shoes on.”

Allene Brown begged him not to start trouble. “I tried to shame him out of it,” she says. “I said, ‘Why don’t you do right?’ He didn’t pay me no attention.”

Roger left Allene Brown’s house just before six o’clock, and came in sight of the Hester farm in time to see Dorothy stepping into a car with a group of black people. He ran up, pulled her out of the car, and confronted her in the road. She ran into the Hester’s front yard, and he followed her. When Barnette Hester stepped between them, he confirmed Roger’s suspicions.

Mama Dora was standing in the road when Roger plunged his hand into Barnette Hester’s side. As he pulled the knife out, she heard him say, “I thought you were going with my wife, and now I know it.”

When Mama Dora turned and began to run, she saw the white men chase Roger into the cornfield. She ran to get Roger Jr., and when she came back to the Hester’s yard, she saw the white men binding Roger’s ankles and wrists. She knew they were going to lynch him. With two-year-old Roger Jr. in her arms, she fled into the woods surrounding Hestertown.

By then, some of the black people who lived in tenant houses on nearby farms had heard the commotion and begun walking toward the Hester house. A white farmer stopped one black couple on the road. “No use in you all going down there,” he warned from the driver’s seat of his car. “We done got him and are going to make away with him.” A few minutes later, the same white farmer told another black man that he’d never see “that black S.O.B. Roger walk this road again.”i If the sight of Roger Malcom bound in ropes, lying in the dirt, didn’t convince them, the white farmer’s comments did. The black people hurried away to tell others that Roger Malcom was going to be lynched.

Then Barnette Hester’s 39-year-old brother, Weldon, drove into the Hester’s front yard. Stepping out of the car, he pushed through the crowd, walked straight over to Roger, and kicked him in the face. Years before, Weldon Hester had lost an eye in a hunting accident, and on this evening-as at any time when he was nervous or angry-his glass eye stared blankly as his other eye cast about. “I am going in and get my shotgun,” he said to the men in the crowd. “Let’s kill him now.”

But Weldon Hester’s mother told him to go to the hospital to see about Barnette. She told him he couldn’t kill Roger Malcom. “You would have to serve time,” she said. “You let the others do it.”

Weldon Hester obeyed his mother and drove off. When the deputy sheriffs arrived, Roger was still lying in the dirt, still alive.

Roger Malcom had never been arrested before, yet he was well-acquainted with Deputy Sheriffs Lewis Howard and Doc Sorrells. The two men had held their positions for nearly a decade; everyone knew them. “They run the county,” people said. “Anything happen in Walton County, they know about it.” At 6-foot-2 and 250 pounds, Lewis Howard was legendary for his ability to withstand pain; after a bank robber shot him point-blank in the stomach with a double-barrel shotgun, he walked into the Walton County hospital holding his intestines. But he was even more legendary for his quickness at the trigger and, according to black people in Walton County, Lewis Howard was quickest when his targets were black men. As the stories went, he’d arrest them and use his gun to make them confess to crimes, whether they’d committed them or not. His partner, Deputy Sheriff E.J “Doc” Sorrells, was also a big man, also known for his reputed tendency toward violence. On this evening, as at any time when he was patrolling the county, he had an unlit cigar clamped between his lips. The last member of the trinity, High Sheriff E.S. Gordon, had held his position since 1933. He was known as a white-haired Wyatt Earp but, at age sixty-seven, he was content to let his deputies handle most matters. So it was the deputies who transported Roger Malcom to the jail in Monroe that Sunday evening.

For Roger Malcom, as for most of the black field hands or sharecroppers who lived and worked on Walton County’s farms, a trip to Monroe was usually a treat. It meant an escape from chopping, hoeing, and picking, and a chance to spend a little money-even though it was usually borrowed from the landlord, and would have to be paid back with steep interest after the cotton settle. For Roger Malcom, it often meant a visit to Standpipe Street, out near the ice plant. There, black men sold jars of liquor out of their houses, and let customers stick around to drink and dance to records. Roger had met Dorothy up on Standpipe nearly one year before.

But on this evening, Roger Malcom wasn’t headed to Standpipe, because he’d stabbed his white landlord. He didn’t know if Barnette Hester was still alive, but he knew he himself wouldn’t live much longer. Tonight or the next night, he would be taken out of jail and lynched. The thick cement walls wouldn’t protect him from a mob of white men.

*** To view sources used in these two chapters, please consult the Notes in Fire in A Canebrake: The Last Mass Lynching in America.